Psychological stress can cause biological damage, such as the release of mitochondrial DNA from damaged and worn-out mitochondria.

Table of Contents

We often hear that stress can be unsettling as it could make us ill when it becomes chronic and overwhelming. However, is there really a biological ratification behind it? Is it scientifically founded? Apparently, independent studies hinted a biological connection indicating how stress can cause biological damage, and eventually lead to certain ailments. And, the mitochondrial DNA — the genome in the mitochondrion appears to play a role.

Biological features of mitochondria

Credit: Boumphreyfr, under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license

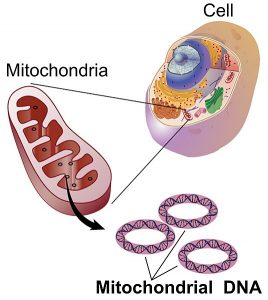

The mitochondrion (plural: mitochondria) is an organelle that supplies molecular energy for various biological activities. In essence, this rod-shaped structure found within the cell accounts for the generation of ATP, the cell’s major energy source. Thus, the mitochondrion is known to be the “powerhouse of the cell“.

Through the process of cellular respiration, glucose (a monosaccharide) is “churned” to extract energy, primarily, in the form of ATP. Firstly, a series of reactions leads to the conversion of glucose to pyruvate. Then, it uses pyruvate, converting it into acetyl coenzyme A for oxidation via enzyme-driven cyclic reaction called Krebs cycle. Finally, a cascade of reactions (redox reactions) involving the electron transport chain leads to the production of ATPs (via chemiosmosis).

The mitochondria have their own genetic material, called mitochondrial DNA. Because of this, the mitochondrion is regarded as semi-autonomous and self-reproducing organelle. It means it can manufacture its own RNAs and proteins. Generally, we inherit the mitochondrial genome maternally, as opposed to the nuclear genome that we inherit from both parents.

Credit: National Institutes of Health

Mitochondrial fate during stress

When confronted with a stressful situation, our body responds intrinsically. We tend to breathe fast. The heartbeat goes wild. Our muscles tense up. And, we sweat profusely. All these responses (so-called “fight-or-flight“) can be an arduous task as they abruptly demand energy. When triggered for so long, eventually, we feel exhausted. Sooner or later, stress sets in and it takes its toll on our health.

The mitochondria work for an extended time just to meet up the spike of demand for energy. In effect, they become vulnerable to damage from too much work. Inopportunely, the mitochondria have limited repair mechanisms unlike the nucleus.1 And in the end, it results in the disruption of the organelle, thereby, releasing the mitochondrial DNA into the cytoplasm. Eventually, the genetic material reaches the bloodstream where they become genet

Mitochondrial DNA cast-offs

The ejected mitochondrial DNA, apparently, becomes genetic wastes and stress might have something to do with this outcome. This theory came about based on a series of studies. Firstly, Gong et al. found that chronic mild stress resulted in mitochondrial damage in hippocampus, hypothalamus, and cortex in mouse brains.2

Secondly, another team of researchers (Lindqvist et al.) reported that individuals who had recent suicide attempt had higher plasma level of freely circulating mitochondrial DNA in blood than those of healthy individuals.3

Thirdly, Martin Picard (a psychobiologist at Columbia University), together with his team, observed similar findings in their participants exposed to a stressful situation. Accordingly, their participants – healthy men and women – were asked to defend themselves against a false accusation. Their blood samples were taken before and after the interview. The researchers found that the mitochondrial DNA in the serum of the participants increased twice 30 minutes after the test. 1 Picard explained that the mitochondrial DNA might have acted like a hormone. Furthermore, he theorized that the ejection of these genetic cast-offs might have mimicked the adrenal gland cells releasing cortisol in response to stress. 1

Mitochondrial DNA as an inflammatory factor

Zhang et al. observed that circulating mitochondrial DNA triggered inflammatory responses. Accordingly, the genetic cast-offs can bind to TLR9 (a receptor) on the immune cell. This binding might have incited the immune cell to respond the same way as they do when reacting with antigens. It might have stimulated the cell to release cytokines that call for other immune cells to the site. 1

So far, these conjectures from independent studies disclose the possible direct biological damage due to stress. There could be a biological insinuation that stress could play a part in the manifestation of ill-health conditions. And, the upsurge of circulating mitochondrial DNA cast-offs is one of them. More information and studies on mitochondrial DNA are delineated on a report on mental health published in Scientific American.

— written by Maria Victoria Gonzaga

References

1 Sheikh, K. (2018 Sept 13). Brain’s Dumped DNA May Lead to Stress, Depression. Scientific American. Retrieved from https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/brain-rsquo-s-dumped-dna-may-lead-to-stress-depression/

2 Gong, Y. Chai, Y., Ding, J. H., Sun, X. L., & Hu, G. (2011).Chronic mild stress damages mitochondrial ultrastructure and function in mouse brain. Neuroscience Letters, 488 (1): 76-80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2010.11.006

3 Lindqvist, D., Fernström, J., Grudet, C., Ljunggren, L., Träskman-Bendz, L., Ohlsson, L., & Westrin, Å. (2016). Increased plasma levels of circulating cell-free mitochondrial DNA in suicide attempters: associations with HPA-axis hyperactivity. Translational Psychiatry, 6 (12), e971–. http://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2016.236