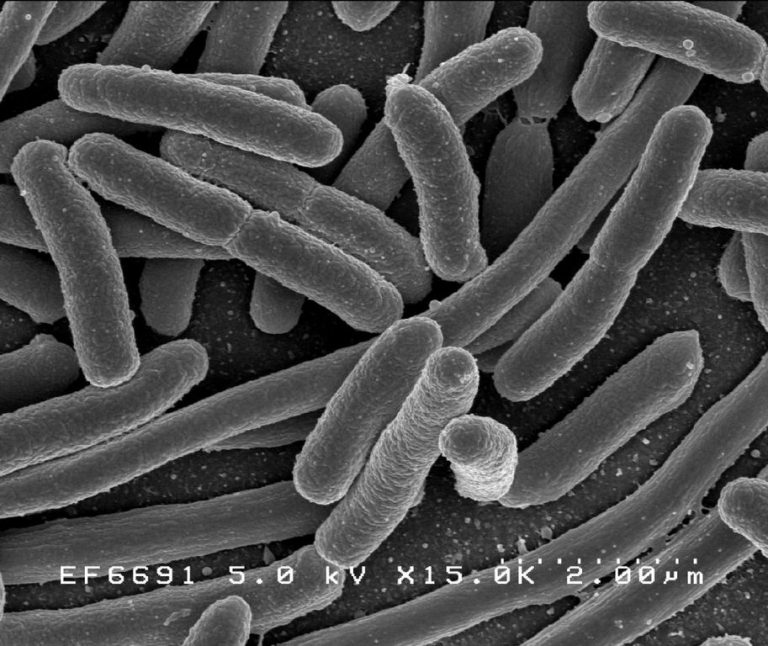

Escherichia coli, one of the many species of bacteria in the human gut

Table of Contents

When sadness reeks in and you feel as if you are all by yourself, think again. That is because you are never alone. As a matter of fact, millions of microorganisms reside in our body day in and out. They are the normal flora. Our body is a world of microscopic living entities that inhabit our body without essentially causing a disease. Rather, they live in us in harmonious mutualism. Thus, our body is not ours alone. Hence, we can say we are not absolutely sterile from the moment we are born.

Normal flora

Typically, the body has about 1013 cells and harbors about 1014 bacteria.1 The multifarious yet specific genera of bacteria that predominate the body is referred to as the normal flora. In essence, the normal flora thrives in a host in a mutualistic lifestyle. The microbes take advantage from living stably in the body. In return, they confer benefits to the human host. For instance, their presence helps prevent other more harmful microbes from colonizing the host. Some of them biosynthesize products that the human body can use. Nevertheless, an immunocompromised host could suffer in cases when these bacteria became overwhelming in number, and thereby cause detectable harm, like infections or diseases.

Normal flora in the gut

Microbes that normally thrive in the gut are greater in density and diversity compared with those in other body parts. Nevertheless, they vary in density depending on the location in the gastrointestinal tract. For instance, the stomach harbors about 103 to 106/g of contents whereas the large bowel of the large intestine has about 109 to 1011/g of contents. The normal flora in the stomach has fewer normal microbial inhabitants due to its acidity. The ileum of the small intestine contains a moderate microbial number, i.e. 106 to 108/g of contents.1

Some of the various bacterial species of the normal gut flora includes the anaerobes, Enterococcus sp., Escherichia coli, Klebsiella sp., Lactobacillus sp., Candida sp., Streptococcus anginosus and other Streptococcus sp.. Some of these bacteria aid in the production of bile acid, vitamin K, and ammonia since they possess the necessary enzymes.

Coexistence

Certain normal gut bacteria can become pathogenic. They could cause a disease when opportunity presents such as when changes in their microbiota favor their growth. Be that as it may, a healthy individual would not be usually harmed by their presence. Thus, question arises — why our immune armies do not, by and large, act against the normal flora as aggressively as they would in the presence of more harmful pathogens.

Karen Guillemin, a professor of biology and one of the authors of a paper that appeared in a special edition of the journal eLife, was quoted3: “One of the major questions about how we coexist with our microbial inhabitants is why we don’t have a massive inflammatory response to the trillions of the bacteria inhabiting our guts.”

“Mutualism factor”

Guillemin and her team of scientists reported that they uncovered a novel anti-inflammatory bacterial protein they referred to as Aeromonas immune modulator (AimA). Accordingly, AimA is a protein produced by a common gut bacterium, Aeromonas sp., in the animal model, zebrafish. The researchers found that AimA alleviated intestinal inflammation and extended the lifespan of the zebrafish from septic shock.2 Furthermore, they described it as an immune modulator that confers benefits to both bacteria and the zebrafish host.

The newly-discovered protein seems to be the first of its kind. Nevertheless, it is structurally similar to lipocalins, a class of proteins that, in humans, modulate inflammation. Based on their findings, the removal of this protein caused more intestinal inflammation in the host and the destruction of the normal Aeromonas gut bacterium. The reintroduction of AimA reverted to “normal”, i.e. the host, relieved from inflammation and Aeromonas’ typical density, restored. AimA appears to represent a new set of bacterial effector proteins. And, Guillemin referred to them as mutualism factors.3

Guillemin and her team postulate that many more of these mutualism factors exist even in humans, and yet to be found. These mutualism factors may have therapeutic potential for use in modulating inflammation especially in medical conditions such as sepsis and certain metabolic syndromes.

— written by Maria Victoria Gonzaga

References

1 Davis, C. P. (1996). Normal Flora. In: Baron S, editor. Medical Microbiology. 4th edition. Galveston (TX): University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston. Retrieved from [link]

2 Rolig, A. S., Sweeney, E. G., Kaye, L.E., DeSantis, M. D., Perkins, A., Banse, A. V., Hamilton, M.K., & Guillemin, K. (2018). A bacterial immunomodulatory protein with lipocalin-like domains facilitates host–bacteria mutualism in larval zebrafish. eLife. [link]

3 University of Oregon. (2018, November 6). Novel anti-inflammatory bacterial protein discovered: Newly discovered protein alleviates intestinal inflammation and septic shock in an animal model. ScienceDaily. Retrieved from [link]