Bone

n., plural: bones

/boʊn/

Definition: Mineralized skeletal tissue

Table of Contents

The bone is an organ that forms the skeleton of vertebrates. It is formed from bone tissues, which are mineralized connective tissues. Other types of tissues found in bone are marrow, endosteum, periosteum, nerves, blood vessels, and cartilage.

Bone Definition

Bone, in biology and anatomy, refers to a specialized, hard connective tissue forming the structural framework of the skeleton. There are different types of bones based on their morphological features: (1) long bones (e.g. bones of the limbs), (2) short bones (e.g. tarsals and carpals), (3) flat bones (e.g. cranium, ilium, sternum, and rib cage), (4) irregular bones (e.g. vertebrae), and (5) sesamoid bones (e.g. patella, pisiform of the wrist, the lenticular process of the incus, first metacarpal bone, and first metatarsal bone).

The primary functions of bones are to provide structural support (act as the body’s framework) and to protect internal organs. In humans, the bone marrow of cancellous bone is the site of hematopoiesis. The bone also serves as a reservoir of minerals, e.g. calcium and phosphorus.

“The Science of Bones – Anatomy and Physiology” by Armando Hasudungan:

Biology definition:

A bone is a rigid organ comprised of bone tissues and forms the skeleton of most vertebrates. The bone tissue is constantly being made and replaced in the process called remodeling. Bones are crucial components of the skeletal system. They provide structural support and protect the softer, internal organs. They also anchor muscles and serve as reservoirs for minerals, such as calcium and phosphorus. They also play a role in blood cell production through the bone marrow.

Etymology: The word “bone” originates from the Old English word “bān,” which can be traced back to the Proto-Germanic word “bainan.”

Synonym: osseous tissue; skeletal tissue

See also: osteoporosis

Characteristics of a Bone

How can we identify that a structure is a bone?

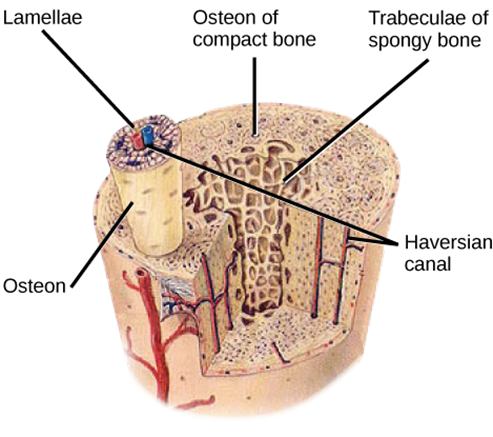

- Hardness and Porosity: One of the characteristics of a bone is its hardness. A biological organ is a bone when it is notably hard and rigid as it primarily provides structural support to the body. Its hardness is due to the calcified tissues (or bone tissues that have undergone mineralization). As for the bone’s porosity, the epiphyses (the trabecular ends of bones) are porous resembling a network of struts and spaces. Thus, the bone consists generally of two layers: the cortical bone (compact bone, which is the outer, hard layer of the bone and with greater bone density) and the cancellous bone (spongy bone, which is the inner, spongy layer of the bone and is less dense but provides critical structural support and accommodates bone marrow).

- Shapes and sizes: Familiarity with the shapes and relative sizes of bones can help identify if a structure or tissue is a bone. Bones come in various shapes and sizes that are adapted to their function. For example, the nasal conchae are the small bones in the nasal cavity that are assembled like scrolls. Such bone arrangement increases the surface area of the nasal cavities, enabling them to better filter and humidify the air as it passes to the lungs.

- Bone marrow: The presence of bone marrow indicates that the organ is a bone. Bone marrow is a soft and gel-like tissue typically found in the central cavities, particularly, of large or long bones. The bone marrow

- Bone matrix: Bones have a bone matrix, which is the extracellular matrix made up of organic and inorganic components. Such a structure can withstand significant mechanical stress while remaining relatively lightweight. In humans, the bones consist more of the inorganic component, which is about 60-65% of the bone’s dry weight; the organic component constitutes only about 35-40%. Bone’s composition comprises an intricate balance of organic and inorganic components, making it a composite material.

- The organic component consists primarily of the collagen-rich organic matrix, collagen fibers, and collagen fibrils.

- The inorganic component mainly comprises calcium phosphate, giving bone its characteristic hardness and strength.

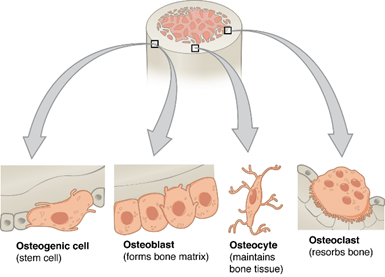

- Cellular components: The primary cells of bone tissue typically include the osteoprogenitors (mitotically active cells), osteoblasts (bone-forming cells), osteocytes (mature bone cells for maintaining bone tissue), and osteoclasts (bone-resorbing cells).

- Osteon: The bone is made up of the fundamental functional unit called the osteon (or the Haversian system).

Bone tissue is a living tissue made up of bone cells, blood supply, and bone marrow. Image Credit: libretexts.org. - Connectivity: Bones often articulate or connect with another bone at joints.

Functions Of Bone

Here are the various functions of the bone:

- Support and framework for the body. Bone provides support to the entire body, such as as an internal structural scaffold, or as a protective case or enclosure for vital or soft organs, such as the skull protecting the brain, and the ribcage protecting the heart and lungs.

- A role in muscle attachment. Bones serve as attachment points for certain muscles

- Mineral storage (calcium and phosphorus). Bones serve as reservoirs for minerals vital in various physiological processes.

- Hematopoiesis (bone marrow). Within the bone marrow, red blood cells and white blood cells are produced, contributing to the body’s immune response and oxygen transport.

Development And Growth Of Bone

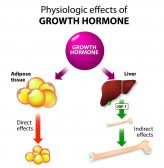

Bone growth and development involve intricate processes, including intramembranous and endochondral ossification. These processes lead to the formation and elongation of bones during embryonic development and throughout a person’s life. Factors such as genetics, nutrition, and hormones affect bone growth.

Read how the bone forms: Formation of the Bone Matrix and Osteogenesis

NOTE IT!

Question: What is the longest bone in the human body?

Answer: The femur, commonly referred to as the thigh bone, is the longest bone in the human skeleton. This remarkable bone extends from the hip joint down to the knee joint, forming a crucial part of the lower limb’s skeletal structure. It houses the bone marrow responsible for producing blood cells. It facilitates a wide range of movements. Its impressive length and robust structure provide essential functions for human mobility and stability.

References

- Gray, H. (1858). Gray’s Anatomy

- Bilezikian, J.P., Raisz, L.G., and Rodan, G. (1996). Principles of Bone Biology.

- Lateral wall of nasal cavity. (2014). Kenhub. https://www.kenhub.com/en/library/anatomy/inferior-nasal-concha

©BiologyOnline.com. Content provided and moderated by Biology Online Editors.