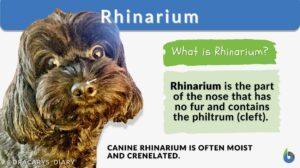

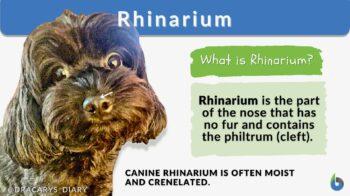

Rhinarium

n., plural: rhinaria

[raɪnərɪəm]

Definition: The hairless skin area surrounding the nostrils in some mammals

Table of Contents

Rhinarium Definition

Rhinarium is the hairless (furless) skin area around the external openings of the nostrils in many mammals. This surface of the skin is usually more or less moist, crackled, or embossed. The rhinarium is part of the olfactory system and is therefore associated with the sense of smell (olfaction).

Word origin: The term rhinarium is a Latin word, meaning “belonging to the nose”

Synonym: nose leather; nosepad; “truffle”; wet snout; wet nose; planum nasale

Structure of Rhinarium

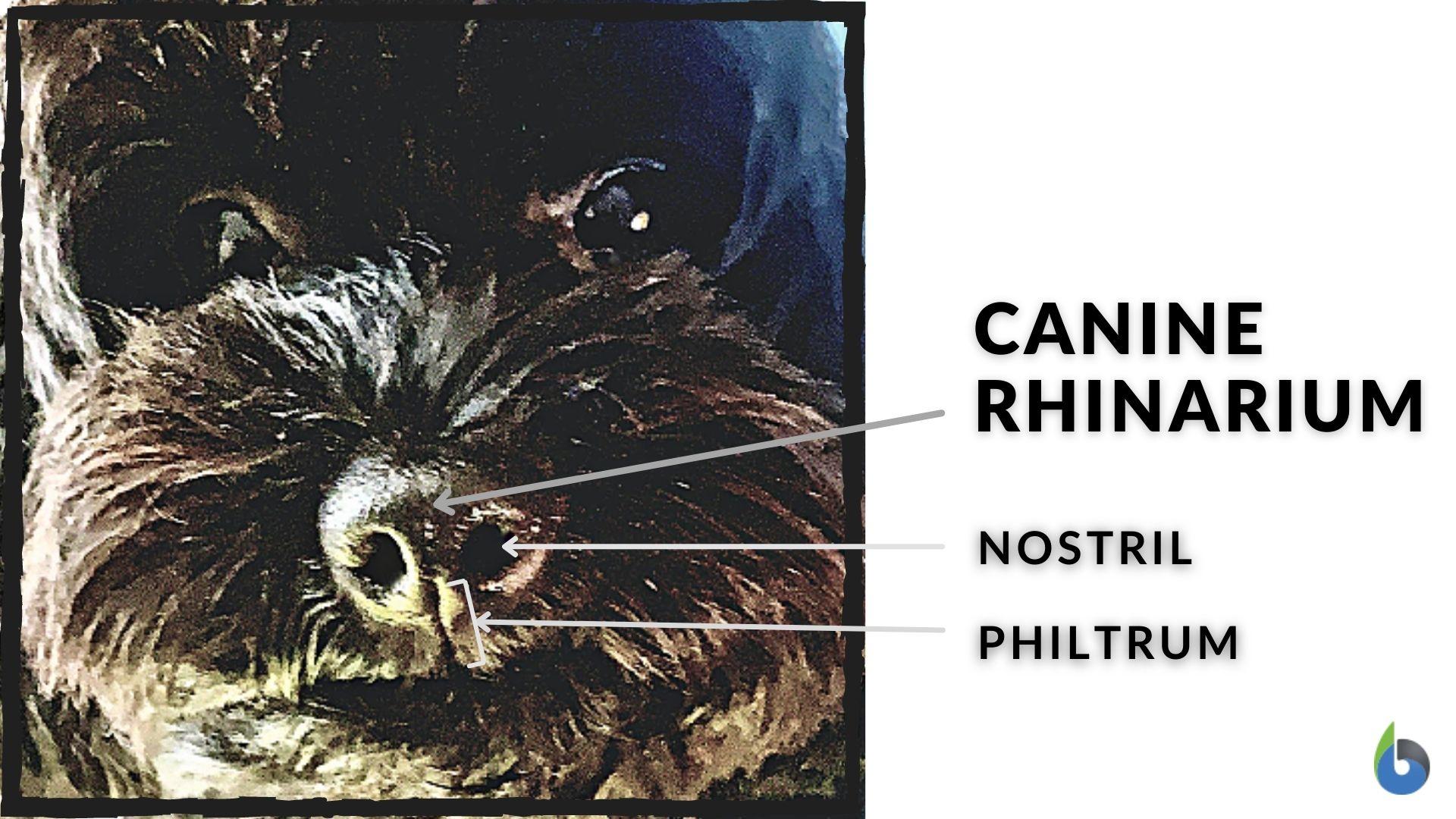

Rhinarium is the part of the nose that has a naked surface, meaning it has no fur but glabrous skin. It has wrinkles on the surface (called crenellations). It surrounds the nares (nostrils where gases are exchanged through the nasal passages — also called nasal cavities).

Most mammals have a groove called a philtrum. In many species with rhinarium, it is located posteriorly, in the middle of the rhinarium to the upper lip.

Watch this vid: why dogs have wet noses…

Functions of Rhinarium

The rhinarium is believed to be involved in the olfactory function (smelling) as many animals with rhinarium are characterized to have a greater acute sense of smell. In many species, olfaction (sense of smell) is carried out by the main olfactory system and an accessory olfactory system. The question is, which part of the olfactory system does the rhinarium belong to? Is it part of the main olfactory system that detects airborne substances or is it part of the accessory olfactory system that detects chemicals dissolved in fluids? The answer remains inconclusive.

Some claims that the rhinarium is a continuation (extension) of the olfactory epithelium (of the main olfactory system). Others believe that rhinarium is sensitive to pheromones and therefore associated with the vomeronasal organ (VNO) that detects liquid organic compounds like pheromones. The VNO is part of the accessory olfactory system that is connected to the philtrum via ducts inside the mouth. It is believed that the nonvolatile odorants may have been conveyed from the rhinarium to the VNO through the philtrum.

Rhinarium serves other purposes in certain animals. In walruses, the rhinarium is covered with bristles that protect, primarily when the walrus forages for shellfish.

The rhinarium also enables wind direction detection. Animals with rhinarium detect smell and identify the direction where the odor is coming from.

Examples of Rhinarium

Examples of mammals that have rhinarium include cows, cats, dogs, elephants, and walruses. Some primates also have a rhinarium. The strepsirrhines (i.e. lemurs, lorises, pottos, and galagos) are an example. Their primitive rhinarium is a feature that characterizes them. Strepsirrhines belong to the suborder Strepsirrhini (or Strepsirhini) of the order Primates. They are also referred to as wet-nosed primates. Other species of Primates lack “wet noses”. They are referred to as dry-nosed primates. They belong to the suborder, Haplorrhini (haplorrhines).

Frequently Asked Questions on Rhinarium

- Where is rhinarium found? Rhinarium is at the mammalian nose tip that has no hair or fur.

- Which primates have a rhinarium? Strepsirrhines (suborder Strepsirhini) are examples of primates with wet rhinarium. They include the lemurs, galagos, lorises, and galagos.

- Do humans have a rhinarium? No. Humans do not have a rhinarium. Humans descended from the lineage of primates that have “dry noses” — the haplorhines of the suborder Haplorhini. Humans do have a philtrum, though, which is a vestigial structure as it has no clear function. The human philtrum is bordered by ridges and typically a depression (not a cleft) below the nose. A medical condition where the philtrum fails to form/fuse during embryonic development is called a “cleft lip”. In other conditions wherein the philtrum is smooth or flattened, this could be a symptom of fetal alcohol syndrome or Prader-Willi syndrome.

Take the Quiz on Rhinarium!

References

1 Dijkgraaf, S., Zandee, D. I., Addink, A. D. F. eds. (1978). Vergelijkende dierfysiologie (Comparative animal physiology) (in Dutch) (2nd ed.). Utrecht: Bohn, Scheltema & Holkema.

©BiologyOnline.com. Content provided and moderated by Biology Online Editors.